Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague

****

Introduction

Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague Leonora Carrington British,1917–2011 Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague, 1955 Oil on canvas Minneapolis Institute of Art Bequest of Maxine and Kalman S. Goldenberg ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Enormous insects, glowing, ghostly figures, the stage-like scene, the strange title: What is happening in this painting?

The words “Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague” appear on the pages of the open book. Also the painting’s title, these words are as curious as the many other intriguing and mysterious details. The artist, Leonora Carrington, did not want her work explained; she seems to have been more interested in the questions it raises.

****

A Non-Conforming "Surrealist"

Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) was born in England into a wealthy textile-manufacturing family that expected her to be presented at court and to marry well. But Carrington was a nonconformist. She rebelled against many ideas, including the notion that her brothers could get away with bad behavior, while she had to be good. Carrington was expelled from several convent schools for her refusal to follow the rules.

Carrington convinced her parents to send her to art school, first in Florence, later in Paris. It was there that she met the painter Max Ernst and, at age 19, they became romantically linked. Her father disowned her, and she gave up her life as a wealthy heiress.

Carrington and Ernst were part of a circle of artists called Surrealists. The Surrealists believed that dreams and the unconscious were superior forms of reality, hence the term sur-real. They often depicted strange juxtapositions in their art, like the people and giant insects in Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague. Many male Surrealists saw women not as artists in their own right, but as muses, or inspiration, for their art. Carrington resisted the idea of being a muse and pursued her own art.

Carrington and Ernst lived and worked together for three years until WWII interfered. When Ernst was arrested for being an enemy German in France, Carrington had a breakdown and ended up in a mental hospital in Spain. After her recovery, she immigrated to Mexico City in 1942. She met other artists, such as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Remedios Varo, and Emerico “Chiki” Weisz, whom she later married.

Carrington refined her unique vision as an artist in Mexico. In her art, places where women were traditionally in charge, such as the kitchen and the nursery, were changed from places of female drudgery to those of power and transformation. Carrington added her own history, culture, and symbolism to the mix to create a body of artwork that did not conform to any category. Although art historians often categorize her as a Surrealist, Carrington did not identify herself as one.

Surrealist artists often juxtaposed seemingly unrelated images in their writing and visual art. In Aphrodisiac Telephone, Salvador Dali challenges the viewer to reexamine what a telephone is by using a lobster as the handset.

Salvador Dali, Aphrodisiac Telephone, 1938, plastic, metal, William Hood Dunwoody Fund. ©Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Surrealism was an international art movement. Born and trained in Minnesota, Gerome Kamrowski moved to New York City in 1938 and joined a group of American artists there who were strongly influenced by many of Surrealism’s basic goals, such as exploring the unconscious to help free the creative imagination.

Gerome Kamrowski, The Competitive Lover, 1945, oil on canvas, John R. Van Derlip Fund

****

I(magic)nation

Fascinated with stories from an early age, Leonora Carrington remembered writing and illustrating magical tales from her own imagination at age 4. As an adult, Carrington would explore the idea of painting as a type of magical practice; mixing the paint is like making a potion, and painting on canvas is creating a new, imagined world.

Carrington’s mother, grandmother, and Irish nanny raised her on Irish fairy tales, mythology, and Catholic mysticism, in addition to imaginative classics such as Alice in Wonderland. She recounted: “My [maternal] grandmother used to tell me we were descendants of that ancient race that magically started to live underground when their land was taken by invaders with different political and religious ideas. They preferred to retire underground where they are dedicated to magic and alchemy, knowing how to change gold.” (Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art, Susan L. Aberth, Lund Humphries, 2010) These ancient people, known as the Sidhe, (pronounced “shee”) are described as slender, beautiful, intelligent, and graceful. They possess magical powers, such as shape-shifting, and live their lives parallel to human society. Perhaps the mysterious people in Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague are the Sidhe?

The figures at the table appear to be playing a game of chance, with a die and a serpent on a ladder—perhaps a reference to the game Snakes and Ladders, which originated in India. They are intent on the game. Or is it a magical ritual?

As a life-long learner, Carrington was interested in developing her own imagination; she continuously sought out ideas, philosophies, and images to incorporate into her visual art. In Mexico, she drew on influences from colonial Spanish as well as Indian culture, healers, and spiritualists, and added these to her knowledge of folk and fairy tales, psychology, and world religions.

When Carrington attended art school in Florence, she became enchanted with Italian Renaissance artists like Fra Angelico. She was intrigued by their use of tempera paint, perspective, and symbolism. Compare the perspective of Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague and The Nativity.

Fra Angelico (Fra Giovanni da Fiesole), The Nativity, 1425–30, tempera on poplar panel, Bequest of Miss Tessie Jones in memory of Herschel V. Jones

Look at the loom on the left side of Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague. Then look at the headdress of the Moche warrior of this vessel. As an artist living in Mexico, absorbing images and ideas from local and international cultures, Carrington may have chosen this design to refer to a Mayan sun symbol.

Peru, Moche, Vessel, 5th–6th century, ceramic, paint, Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund

****

Microcosm & Macrocosm

Carrington was obsessed with details and precision in her work. She painted everything carefully, down to the feathery hair of the human characters and the translucent wings of the insects. But she is also concerned with big ideas. In Down Below, a personal account, she wrote: ""The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between Big and the Small, which makes it impossible to see the whole. To possess a telescope without its other essential half—the microscope—seems to me a symbol of the darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope."" (The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below, Leonora Carrington, E.P. Dutton, 1988, page 163)

In Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague, Carrington juxtaposes small details with big ideas such as fate or chance, and metamorphosis or change. The detail of the egg on the table leg perhaps refers to the idea of macrocosm and microcosm. Instead of a telescope or microscope, Carrington has given the woman on the right a lorgnette (a handheld viewing glass; in French, "to peer at, or to look in a sidelong glance"). Did she just come from the opera? Is she simply getting ready to look at something more closely? Maybe has she removed it, to avoid seeing?

The human (or Sidhe?) characters are strange enough, but scattered around the room are insect characters in various stages of metamorphosis, seemingly observing, helping, or affecting the outcome of the scene. The insects' scale is huge when juxtaposed with the other characters. While many people view insects as pests, these giant insects seem to go about their business largely unobserved. There is an adult moth on the column at right. On the left is a precariously balanced contraption that looks like a loom. Moths are well known for destroying wool, so is the moth a threat? Are the insects on the loom attacking the fabric, or are they weaving? The insects on the ceiling appear to be adult mayflies, known for their abundance and short lifespan. What Big ideas might Carrington be referring to with these Small details?

Still Life by Pieter Claesz appears simply to depict a feast. But by including the watch, Claesz reminds us of the concept of time; we notice the fine meal has been interrupted, and perhaps the dinner left unwillingly, and in a hurry.

Pieter Claesz, Still Life, 1643, oil on panel, The Eldridge C. Cooke Fund

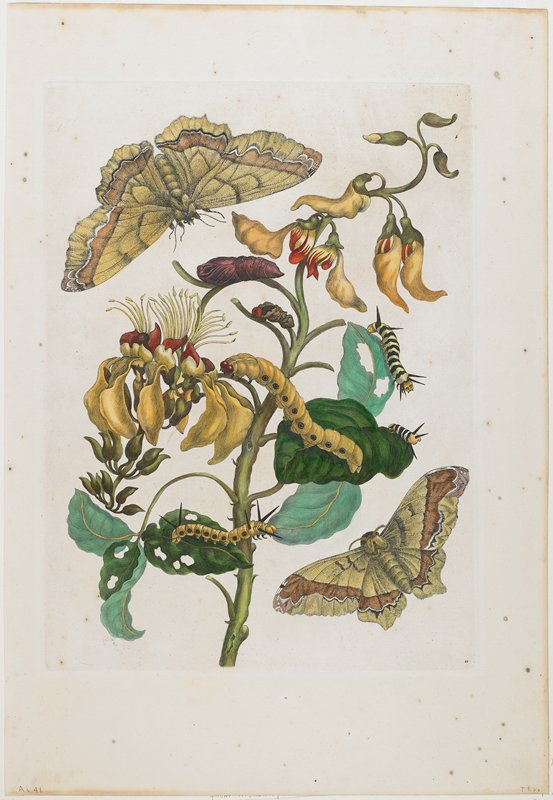

Maria Sibylla Merian studied insects in the 18th century. She magnified the size of the insects and flower, so viewers can see all the details and experience the insects' world.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Caterpillars, Butterflies and Flower, 1705–71, hand-colored etching and engraving, The Minnich Collection, The Ethel Morrison Van DerLip Fund

Maria Sibylla Merian studied insects in the 18th century. She magnified the size of the insects and flower, so viewers can see all the details and experience the insects' world.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Caterpillars, Butterflies and Flower, 1705–71, hand-colored etching and engraving, The Minnich Collection, The Ethel Morrison Van DerLip Fund

The insects in this French still-life painting invite the viewer to look closer to see that things are not as they first appear. The butterflies and caterpillars allude to the impermanence of earthly things.

Abraham Mignon, Still Life with Fruits, Foliage and Insects, 1669, oil on canvas, Gift of Bruce B. Dayton

****

Related Activities

Dream a Little Dream

This painting has a dream-like quality. Make your own artwork, showing a dream that you had, or invent a dream. What colors will you choose to represent your dream? Or do you dream in black and white?

Games of Chance

Play the game Chutes and Ladders, or the original Snakes and Ladders. What makes these games of chance? In both games, the snakes (or chutes) refer to bad behavior, and the ladders to good. The games teach morality lessons and show life’s journey being complicated by a random dice roll. Refer to the Wikipedia page on Snakes and Ladders, and play the impartial, non-chance game mentioned in the Mathematics of the Game section.

Shapes & Lines

This painting is very dynamic. The artist has chosen to set the scene at an angle, which focuses attention on the seated woman on the far left. Notice the repeated use of triangles (tables, loom base) and the triangle of the ceiling formed by the “cutaway” scene. To see how Carrington used the artistic principles of line and movement, look at the insects in the lower-left corner, then follow the action to the loom, to the figures at the table, to the bust on the pedestal, and finally to the woman by the curtain.

Dear Diary

Pretend you are the writer of the diary in the painting, continuing from the words in the book Dear Diary—Never Since We Left Prague. What happens in the following pages?

The Play's the Thing

This scene is very theatrical. The people and insects are characters, they inhabit a set, and have props and costumes. It's as if it is a moment frozen in time, and we are interrupting it. What was being discussed in this scene before the woman on the right (and you) walked up? Name each character and write a short, 10-minute play that brings the audience up to the point in time of the painting. Assemble at least seven classmates, read the lines, and act it out. Freeze-frame the characters at the end, in their positions of the painting.

Surrealist?

Leonora Carrington is often identified as a Surrealist. Visit Mia to check out the collection of Surrealist art. What do you notice about it? Write a definition of Surrealism from what you see. Or choose an artwork and write a poem or description of it. It is easy to request a school tour online.