Making Peace

These five diverse artworks represent stories about peace

Fact One: Inner Peace

Ernst Barlach

German, 1870–1938

The Fighter of the Spirit, 1928

Bronze

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Look closely at this statue. What about it might make someone so angry, they would want to cut it apart and melt it down?

Called The Fighter of the Spirit, the sculpture was made by Ernst Barlach, one of the most important German sculptors after World War I. He created it in 1928 for the university church in Kiel to honor students killed during WWI. Though he initially supported Germany’s role in the war, the terrible bloodshed and suffering he witnessed turned him into a pacifist--a term for one who seeks peace.

This war memorial emphasizes the dignity, suffering, and spiritual power of individuals who thought for themselves. That made the Nazis, who took over Germany in 1933, angry. The Nazis realized that some art was so powerful, it could change the way that people think about war. And they wanted every German to be devoted to the Third Reich and to help carry out their plans to invade and conquer other countries.

So they decided to destroy this statue. You can see the saw-tooth marks midway on the body where the angel was cut in two. However, instead of melting it down as ordered, someone hid the pieces in a local museum, from which Barlach’s assistant bought it. He sold it to a university student, who concealed it until the war ended. After World War II, Barlach’s admirers cast new versions of the statue in bronze from the pieces. The sculpture that now stands outside of the Minneapolis Institute of Art is the only known full-sized cast from the original.

Barlach believed that much suffering is caused by human greed, ambitions, and self-deception. Some think this statue is a metaphor for justice; the lion symbolizes strength, and the angel protects the innocent.

This statue has become a symbol of the power of peace over injustice and war.

The Avenger. Ernst Barlach, The Avenger,

modeled 1914, cast 1923,

bronze,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

gift of the P. D. McMillan Land Company

At first, Barlach was an enthusiastic supporter of Germany’s role in World War I, as visible in this early sculpture.

(Detail) Ernst Barlach

German, 1870–1938

The Fighter of the Spirit, 1928

Bronze

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

The face of Barlach’s figure contributes to the sculpture’s message of peace.

Käthe Kollwitz, Battlefield, plate 6 from the Peasant’s War cycle,

1907 (1921 edition),

etching and soft-ground etching, with half-tone screen,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund

Käthe Kollwitz, a German printmaker and pacifist, was a firm believer in the resilience of the human spirit. She made many woodcuts, lithographs, and other prints that show the inner strength of women, especially mothers, during World War I and II.

Fact Two: Peacemaker

Attributed to José Montes de Oca Spanish, 1675 –1764 Saint Benedict of Palermo, c. 1734 Polychrome and gilt wood, glass Minneapolis Institute of Art The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Are you, or do you know, a peacemaker—someone who takes action to make peace? St. Benedict of Palermo was such a person. Born in 1524, he is still remembered today for his peaceful ways.

The first Christian saint of African origin to be canonized in modern times, Saint Benedict of Palermo (1524–89) was born in Sicily (then part of Spain) to parents who were probably from Ethiopia and formerly enslaved.

Granted freedom at age 18, Benedict continued to work for his former master. He earned a meager wage, much of which he gave to people who were sick and in need. Nonetheless, he was often bullied for his black skin. He responded with peaceful actions and gentle words. He later joined a religious group called the Franciscans. He was admired as a model of religious devotion, wise counsel, and leadership. Benedict had a strong sense of community and referred to possessions as “ours” not “mine.”

His death inspired a grassroots movement that resulted in his sainthood. By the early 1600s, Saint Benedict was widely venerated in Italy, Spain, and Latin America. Today he is considered the patron saint of African Americans.

When you look at José Montes de Oca’s wooden statue, carved in Sevilla in the 1730s, what do you see that brings Benedict’s peaceful, inspiring personality to life? Created to appear lifelike, his shining eyes made from glass paste look directly at the viewer. He seems as if to speak; his open mouth reveals teeth made from bone. The welcoming gesture of his spread arms, the gentle movement of his garments, and the turn of his body also show his vitality. Is he, with great emotion, asking us to follow his peaceful example?

Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,

just before he spoke at the funeral of the four girls murdered in the 16th Street Baptist Church.,

1963

Danny Lyon

gelatin silver print (printed 1999)

The Alfred and Ingrid Lenz Harrison Fund

Danny Lyon, photographer and peacemaker, documented the American Civil Rights Movement in hundreds of photographs, including this one of peacemaker Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Danny Lyon, American, born 1942, Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., just before he spoke at the funeral of the four girls murdered in the 16th Street Baptist Church, 1963, gelatin silver print (printed 1999), Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Alfred and Ingrid Lenz Harrison Fund

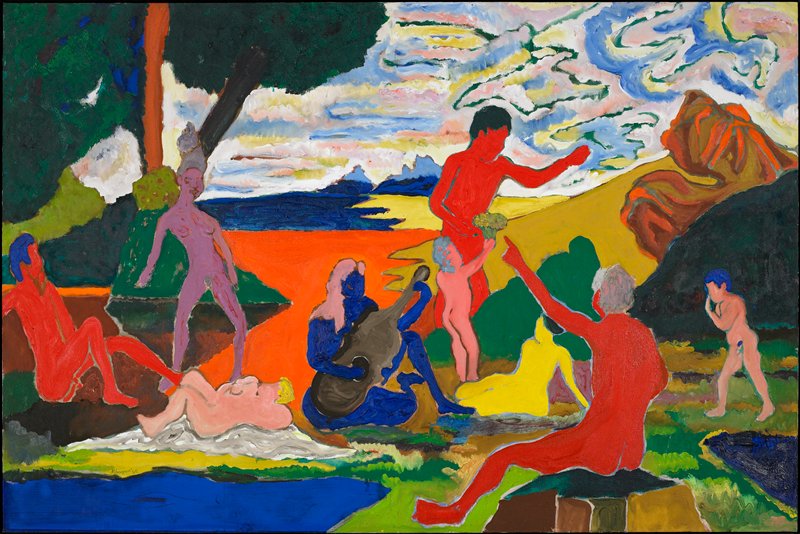

Homage to Nina Simone,

1965,

oil on canvas,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Bob Thompson celebrates his hero, Nina Simone, a singer, songwriter, and Civil Rights Movement peacemaker, in this colorful painting. Bob Thompson,

Jizō, the Bodhisattva of the Earth Matrix,

early 13th century

Unknown Japanese

Wood with polychrome, lacquer, and gold; metal

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of funds from Anne de Uribe Echebarria in honor of her husband, Luis de Uribe Echebarria, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Burke Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke, The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund, and The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Jizo Bosatsu, a divine being of infinite grace and compassion, offers peace to women, children, and others in need.

Fact Three: Peace on a Plate

Persia (Iran)

Plate, early 18th century

White earthenware with underglaze blue and black décor

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Katherine Kittredge McMillan Memorial Fund

Have you ever spent time in a garden so peaceful, you felt you were in paradise? This is the kind of garden envisioned by the artist who painted this plate.

Plates like this were used a long time ago in Persia (now Iran). During a Muslim celebration called Yalda, held on the longest night of the year, family and community members gathered to eat specially prepared foods served on beautiful plates like this. Just like today, they shared stories of their common history and strengthened their relationships with one another.

What about this plate looks special to you? Observe its elaborate blue decoration. Notice how the rim is not smooth but has a leaf-like design. Other details are also significant. The widest band around the center contains a floral, vine-like motif. In the center is a spotted deer with antlers, a symbol of long life, lying in a peaceful garden of enormous flowers and leaves. These designs are a mixture of Islamic and Chinese symbols. In Islamic design, gardens are associated with paradise, a word from Old East Iranian, which means a place of peace, prosperity, and happiness. An Islamic garden, a place of reflection and renewal, is often contained within a wall, as the central image on this plate is contained within a band of decoration.

But how did a Persian plate end up with Chinese designs? Peaceful trading partnerships were conducted along a much-used route called the Silk Road. Chinese potters were aware of and admired the deep-blue ceramic glazes used by the Persians. China imported cobalt ore to create its own blue-and-white porcelain wares during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The Persians greatly admired these dishes, importing large quantities of them. Persian artisans repeated some of the designs they saw, as shown in this plate, but were unable to duplicate the delicate porcelain clay body. Chinese artisans taught them some, but not all, of their secrets. Still, this represented a true artistic exchange, which was only possible between people who were living at peace with one another.

Hubert Robert, The Rustic Bridge, Château de Méréville,

France, c. 1785,

oil on canvas,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Hubert Robert depicts a fanciful French estate garden designed with elements of English landscapes and Chinese gardens to create an environment filled with peace and wonder. To create this garden paradise, a decade-long undertaking, marshes were drained, a mountain was moved, and a river was rerouted into a sinuous, winding course.

Belgium, Allegorical “Millefleurs” tapestry with animals,

c. 1530 –45,

wool and silk,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

gift of Mrs. C. J. Martin in memory of Charles Jairus Martin

Medieval gardens were spiritual places that represented paradise on earth. Millefleurs (thousand-flower) tapestries depicting gardens filled with symbolic plants and animals became popular in the late Middle Ages.

China, Imperial deep dish,

1403 –25,

porcelain with cobalt blue decoration under a clear glaze,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

This Imperial dish exemplifies the Chinese court’s appreciation for blue-and-white porcelain during the early Ming dynasty.

Fact Four: Imagining Peace

40, 1993-2001

Cy Thao

Oil on canvas

Gift of Funds from Anonymous donors

Think about the places in your life that make you feel the safest and the happiest.

In what ways is this scene, by Minnesota painter Cy Thao, like a place you’ve been? What about the picture appears peaceful? What does not? With bright, warm colors and images of children playing in a schoolyard, Thao depicts a life unimaginable to members of his Hmong family—and to him, before arriving in Minnesota at age 7. Prior to emigrating, most Hmong children had never been to a school, making it difficult for them to fit in once in the United States. Thao’s depiction of two children bullying a Hmong child because he looks different and does not speak English reinforces the continuing need to secure peace.

This picture is one of a series of 50 paintings by Thao that tells the 5,000-year history of his people, the Hmong. As a student at the University of Minnesota, where he studied art and political science, Thao yearned to learn about who he was and where he came from. And he wanted to share those stories with Hmong children to remind them—and himself—of their brave ancestors. He tells this complex history in a colorful storyboard format, with each scene expressing an emotion—fear, betrayal, delight, anger—he felt as a young person without a peaceful home.

Thao started the series by painting the Hmong people’s creation stories from their origins in China. Then he followed their migration to Laos, where they helped the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) fight a secret war in Southeast Asia. When the Americans left in 1975, their enemies punished the Hmong for aiding the Americans. No longer were they safe in Laos. Thao’s family landed in a refugee camp, where they stayed for five years. For entertainment, Thao drew pictures in the sand with a stick. Later, as an adult, he used that same child-like quality with a birds-eye view to depict Hmong history.

In painting his Hmong series, Thao shows us how brave, resourceful, and resilient human beings can be in seeking a home that is safe, secure, and peaceful.

In image #24 of his series, Cy Thao shows the last American C46 taking the Hmong military officers from Laos to Thailand, leaving the rest of the Hmong behind.

In image #33 of his series, Cy Thao illustrates how Hmong people blew up plastic bags or made bamboo rafts to cross the river to escape Laos.

In image #43, Cy Thao pictures the Hmong celebrating the New Year in snow-covered Minnesota.

Fact Five: A Promise of Peace

Democratic Republic of Congo

Kongo people

Nkisi Nkondi, late 19th century

Wood, natural fibers, nails

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund

What would it be like if you and your community had a single object to help solve problems, stay healthy, and maintain peace? What would such an object look like? What qualities would it have?

This carved figure’s raised arm, sharp surface, intense stare, and assertive stance might not immediately communicate “peace” to many people today. To the Kongo people who used it in the late 19th and early 20th century, however, the sculpture held the promise of peace. They counted on this aggressive-looking figure to help solve their most troublesome crises, such as healing the sick, protecting the village, ending natural disasters, or getting revenge on someone who misbehaved.

The Kongo people in Africa’s Democratic Republic of Congo and their neighbors call figures like this nkisi nkondi, which means “medicine/night hunter.” A sculptor carved this figure in the fierce pose of a hunter. But this hunter did not hunt animals; it hunted knowledge and the truth. The nkisi nkondi was regarded as a powerful spiritual being that would hunt down people who caused trouble or broke agreements in the community.

“Medicine” refers to materials hidden in the figure’s head, collar, and abdomen by a ritual specialist (much like a doctor, religious leader, and counselor, all in one) to empower the figure to help people engage with the spirit world. The medicines might have included dirt, stones, leaves, seeds, fur, and feathers, all believed to have qualities that lent supernatural power to the figure, not unlike special stones or other objects frequently kept for good health or luck.

The nkisi nkondi, which once held a small knife or spear in its raised arm, combines powers of healing and punishment. With the assistance of the specialist, those who counted on the spiritual power of the figure gathered around it to discuss problems and develop solutions. To ensure that the nkisi nkondi would enforce settlements, the individuals drove sharp objects like a nail or blade into it. They believed that the figure’s spiritual power was so great, they’d better keep their promises.

The Kongo community relied upon the figure and the forces associated with it to maintain social harmony—or peace.

Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light,

12th century

Unknown Japanese

Wood with lacquer and gold

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light, is one of the most popular deities in Asia. To his worshippers, he promises the possibility of life in Paradise without the pain and suffering of this world. The Amida Buddha’s raised right hand disperses fear, and the lowered left hand is open in the gesture of giving or “wish granting.” Japan, Amida Buddha, 12th century, wood with traces of lacquer and gold, Minneapolis Institute of Art, The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Fork, from a two-piece cutlery set, Unknown artist

late 16th century

Italy

Coral, brass, niello, silver, iron, gold

Gift of Funds from the Decorative Arts Council with Proceeds from the 2008 Antiques show and sale

People in the 1500s believed coral to be an antidote for poison; thus, this cutlery set would have offered its user special protection during a meal at the table of a rival family. Italy, Two-piece cutlery set, late 16th century; coral, brass, niello, silver, iron, gold; Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of funds from the Decorative Arts Council with proceeds from the 2008 Antiques Show & Sale.

Portrait of George Washington,

c. 1820

Thomas Sully

Oil on canvas

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

In this portrait, the right hand of U.S. President George Washington rests on a copy of the Constitution, a contract to ensure the protection and well-being of United States citizens.

Related Activities

Peace Poems

Write a poem to describe the most peaceful place you have been, your favorite peacemaker, or your solution for achieving peace in your own community—or the world! Choose descriptive words that will help readers imagine what your place, person, or solution look like.

Peace Exchange

Share your dreams of peace with others. Create 6" x 8" artworks and share them with children from Ghana, Colombia, and Nepal. Visit The Create Peace Project to learn how!

War & Peace

Continue your exploration of peace by searching Mia’s website for additional images related to peace in the collection. Then, search for images of war. Pick one of each to compare and contrast. Think about the colors, images, lines, and materials used.

Language of Peace

Research the word for peace in multiple languages. Then make cards, posters, and flags to share your findings. Shalom.

Peace Flags

In words or pictures, create positive wishes for yourself, your family, classroom, friends, community, or the world. Make a wish for an individual, or celebrate a concept you would like to see throughout the world (e.g., peace, equality, compassion). Inspired by Tibetan Prayer Flags, the Peace Flag Project website shares instructions on the creation of peace flags.