Don't Knock Wood

Explore the versatile art of wood from around the world.

****

Fact #1: A Play on Wood

What do you notice first about these five bats? Why do you think the artist decided to make what he calls "rejects"?

Artist Mark Sfirri's wood art is characterized by a sense of humor and whimsy. In Rejects from the Bat Factory, he plays with a symbol of the great American pastime, the baseball bat. He created the "rejects" from ash, just as real baseball bats are, and burned in the title, artist's logo, and the reason for each bat's rejection, such as CURVED, OVER TEMPERED, and SEMI-PROFESSIONAL. Some of these terms are used in the game of baseball itself.

Sfirri works with a technique called woodturning; he rotates the wood on a lathe while holding the tool that shapes the wood stationary. He uses a particular approach, called multi-axis woodturning, to make traditional wood objects such as bowls and spindles into sculptures. He uses a lathe to manipulate the wood using multi-axis spindles and a series of crosscuts.

To envision how a final product will look with various axes, Sfirri sometimes sketches his ideas on paper, cuts the sketch in pieces, and then repositions them. He more often makes what he calls "3-D sketches," actual wooden objects turned on his lathe, to get an even better idea of how the final artwork could turn out. Click here to see a YouTube video of Sfirri in action.

Sfirri started creating "Rejects" in 1992. His 5-year-old son, Sam, asked him to turn a bat that had a hollow in the barrel end of it like one he had just seen on television during a Philadelphia Phillies game. Sfirri made the bat, and Sam happily went off to play with it. Sfirri was inspired to take the idea further. He explains: "I thought about how it was such an elegant form, so perfectly proportioned as a purely functional object. I then thought that I could take some of my multi-axis turned elements and superimpose them on this readily recognizable blank canvas." (Conversations with Wood: The Collection of Ruth and David Waterbury. Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2011.) By "canvas" he meant the recognizable form of the baseball bat. The multi axes are visible in the twists and shifting positions in this sculpture.

Look at the humorous bats again to see where you think Sfirri repositioned each bat during the wood-turning process.

; end of handle off center; burned logo with title and artist's name; "OVER TEMPERED" and "SEMI-PROFESSIONAL" also burned into bat; c: baseball bat with handle at each end, meeting off-center at middle; d: baseball bat with 2 flattened areas opposite 2 rounded areas at widest point; burned logo with title and artist's name; "ODDLY TEMPERED" and "HARDLY PROFESSIONAL" also burned into bat; e: baseball bat with central inverted section (small end and large end reversed) and 2 disjointed areas; burned logo with title and artist's name; "OVER TEMPERED" and "UN-PROFESSIONAL" burned into bat; f: asymmetrical rack for displaying bats; angled edges](https://1.api.artsmia.org/800/60803.jpg))

Fact #1 caption/s

This intricate wooden cricket cage is one of many objects at the Minneapolis Institute of Art made to support a centuries-old competitive cricket (yes, the insect!) culture in China. Other objects include cricket ticklers, nets, fighting rings, feeding dishes, incubators, traps, sleeping containers, and carriers.

John Bradstreet, a designer, trendsetter, and one of 25 founding members of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, made this card table using his own variation of the Japanese jin-di-sugi technique for aging cypress. He chemically treated the wood and then carved decorative patterns into the surface.

Every seven years, puppeteers from the Ibibio Peoples' Ekong Society in Nigeria used wooden puppets like this one in playful, but satirical, performances to reveal and denounce quarrels, shortcomings, and rivalries in the community.

****

Fact #2: A Celebration in Wood

Look closely at this wooden sun mask made by a Kwakwaka'wakw (kwak-wak-ya-wak) artist. What about the mask suggests the power of the sun to you?

Masks are an important aspect of celebrations among the Kwakwaka'wakw and other Native American peoples in the Northwest Coast region of North America. This elaborate and expressive mask made over 150 years ago likely belonged to a wealthy, noble family who owned exclusive rights to use it. One of only two sun masks known to scholars today, it probably appeared at potlatches—ceremonies that reinforced the tribe's lineage and social hierarchies. The mask celebrates the sun's role as creator and sustainer of life, an important element in performances that tell the origin story of the Kwakwaka'wakw people.

Abundant Northwest Coast forests provide wood for houses, canoes, storage chests, and more. The many birds and animals that inhabit these forests serve as inspiration for Kwakwaka'wakw masks and objects. The artist carved wood away from the log to create the mask shape and the contours of the facial features. Once the carving was complete, the artist used natural earth pigments to emphasize the expression of the sun.

The features of this Sun Mask are characteristic of Kwakwaka'wakw woodworking today. Bold patterns in green, red, black, and white accentuate the forehead, eyebrows, eyes, nose, and mouth. By combining a human nose and bird beak, the artist reminds viewers of the important connection between humans, animals, and the world of the spirits. The copper sunray attachments on this mask are unusual, as most Kwakwaka'wakw masks are made entirely of wood and pigments. In what ways do the additions of copper, perhaps salvaged from a European or American ship, enhance the impression of the sun's power?

Imagine the copper catching and reflecting the brilliant rays of the sun while the dancer moved around, and raised and lowered his head.

)

Fact #2 caption/s

Kachinas are spirits who look over the Hopituh people. This wooden kachina of Pahlik Mana (Butterfly Maiden) celebrates the idea of regeneration through symbolic images, including rain clouds in her headdress and the rectangular design of an ear of corn on her forehead.

Wooden keros, ceremonial vessels used by the Inka peoples, were especially popular during the period of Spanish colonial rule (1533-1821), perhaps because the Spanish had taken most of the precious metals in the region. This kero shows Spanish and Inkan soldiers, Inkan textile designs, and regional plants and animals.

Wooden objects like this model boat survived for centuries, protected from the elements in the tombs of important Egyptians. Ceremoniously buried with other useful objects, the model boat was thought to safely transport the eternal spirit (ka) of the deceased to the next world.

****

Fact #3: The Beauty is in the Wood

Where do the women and girls in your family store their makeup? Do they use a special drawer in the bathroom, a dressing table in the bedroom, or possibly a small bag in their purse?

A woman living in China during the Ming dynasty (late 16th-early 17th century) stored her cosmetics in this decorative wooden cabinet. She used the drawers to hold lip balms, powders, combs, and the many hairpins needed to hold her elaborate hairdo in place. Imagine her slowly lowering the S-shaped easel in the cabinet’s front in order to use the mirror it held. The large size, elaborate decoration featuring royal symbols like the dragon and lotus flower, and throne-like shape all suggest the owner of this cabinet was part of the Emperor's household.

Look carefully at the construction of the cabinet and its decoration. The cabinet is made of a rare and very hard wood found in China called huang-hua-li, which means yellow flowering pear wood. Only highly skilled craftsmen were allowed to make furniture from this wood for the imperial family. The wood’s beautiful warm color and grain remind the viewer of the tree trunks from which it was made. Huang-hua-li was also a good choice for the cabinetmaker; it provided a sturdy material for the construction of drawers and the carving of elaborate decoration that would last over time.

The carvings create many textures; the cabinet would have been a joy to touch. Imagine tracing the flower designs with your fingers or wrapping your hand around the dragon’s head. The textures invite us to look closely at the designs, such as the mythical phoenix on the drawers, which symbolizes the woman’s important role as the mother of heirs to the throne. The dragon symbolizes the vigor and power of the emperor.

This cabinet remains an impressive example of how wood served both a useful and decorative purpose in creating a storage place for the beauty needs of an important Chinese woman.

)

Fact #3 caption/s

This chair is another example of decorative furniture made of huang-hua-li wood during the Ming dynasty. Notice that the lotus flowers—symbols of purity—on the chair's footrest are the same flower used on the cosmetic cabinet's railing posts. China, Folding Round Back Chair, late 16th century, huang-hua-li hardwood with iron hardware, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

)

The back of this throne for the emperor resembles the back of the cosmetic cabinet. Although this throne was made at a later date during the Ch'ien Lung dynasty, it also demonstrates the cabinetmaker's skill in carving an open-work back.

Red lacquer, a wood product made from the sap of a Chinese variety of the sumac tree, was used to give this small chest its red color. The doors open to expose six drawers for storing cosmetics.

****

Fact #4: The Many Wonders of Wood

Have you ever seen a gigantic wave on the ocean? Or on one of the Great Lakes? Seeing such a wave must be a memorable event since some can be reach as high as 30 meters (about 100 feet). Personal experience may have inspired artist Katsushika Hokusai to create this image, Under the Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai made at least two other images of this wave before he created this masterpiece, which may be the best-known work of Japanese art in the world.

Hokusai was a successful artist during Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868) and became well known for his ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He created this image in the 1830s to sell to the common people of Japan; it was the first in a series, called Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. The print was an instant success! It shows a 12 to 15 meter high otinami (“wave of the open sea”) off the coast of his home district, Kanagawa, Japan.

Hokusai juxtaposes the huge breaking wave threatening to engulf three boats with a tiny, calm, snow-clad view of Mount Fuji in the background, both at the center of the wave as well as of the image. The print is notable for being one of the first to use a new chemical pigment called Berlin Blue, which produces a deep blue that does not fade with time as one can see in the print’s still-vibrant blue water.

So, where’s the wood? The print is called a woodcut because it was made using the oldest known printmaking technique of carving an image out of a block of wood. Each of Hokusai’s images is created from many different blocks of fine-grained cherry, one for each color. Hokusai likely made the original line drawing for the image using black ink made from pine soot. The carvers and printers who worked to create this print used tools made from wood or with wooden parts. And finally, the paper used for the print was made from the inner bark of the mulberry tree, and some of the inks used were derived from tree-based dyes.

Hokusai’s iconic image of the “Under the Wave” is a testament to the talent of the artist and the wonderful versatility of wood.

Fact #4 caption/s

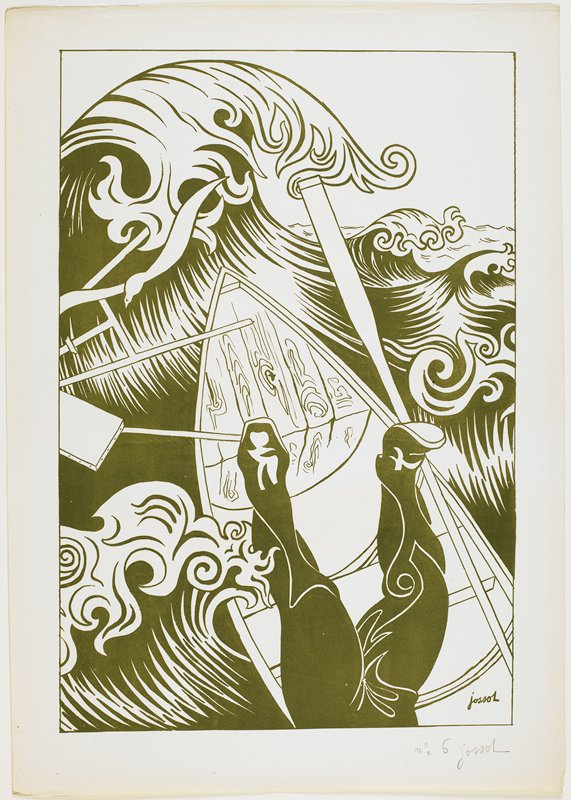

In The Wave, Henri-Gustave Jossot, a French caricaturist at the end of the 19th century, jokingly makes a statement about his fellow artists who have become enamored by Japanese art. His print depicts a painter in a boat that's being upended by a wave very much like the one in Hokusai's Under the Wave off Kanagawa. Henri-Gustave Jossot, The Wave, 1894, lithograph printed in olive green ink, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edward A. Foster, 1965 p.206

In this woodcut, Käthe Kollwitz utilized the grain of the wood plank to create the sense that the two women are united in a single form. The figures, who seem to emerge from the dark background, appear to have been scraped along this grain.

****

Fact #5: Musical Wood

Look closely. You will discover that this entire drum is made of a single piece of wood!

The Iatmul (yaht-mool) people of Papua New Guinea believe that they were born from a great ancestral crocodile, Wagen. In their lore, Wagen continues to carry the earth on its back, creating earthquakes and rivers by swishing its giant tail. Wagen, one of 20,000 ancestral animals of the Iatmul, appears on this hand drum, which was used in ceremonies to celebrate ancestors and remind the community of its origins. Wood instruments like this one usually include fantastic carved designs that refer to an array of creatures and ancestral beings.

Look for several carved representations of a crocodile on this drum. At each end of the drum is a carving of the open jaws of a crocodile. These open jaws remind the Iatmul of the sky and the earth, which in this drum are linked by another crocodile used as a handle. The carved and painted geometric designs, including rows of small spikes on the sides, represent the skin and teeth of the crocodile ancestor.

Kundu drums are used in events and ceremonies that include not only music, but also dance and theatrical performance. The drum sound represents spirit and ancestor voices. One ceremony celebrates young males' passage from boyhood to manhood, which also includes a performance in which the men represent Wagen by dancing in a long line. Some Iatmul groups even make huge basketry masks of the great crocodile. The young boys then pass through the crocodile mouth to mark symbolically the death of their childhood, and birth into adulthood. The kundu drum is beaten in rhythmic accompaniment to the songs and dances of the initiation.

While making a drum, the Iatmul carver speaks special words to invite ancestral spirits to enter the work and thus give it power in the community. When spiritual power is transferred to newly carved drums, the old ones lose their former value.

Fact #5 caption/s

This rattle, once owned by an important Haida leader, takes the shape of Raven, who, according to many Northwest Coast creation stories, stole the sun from its hiding place and put it in the sky.

The Ch'in is probably the world's oldest musical instrument that continues to be played today. This ch'in, made from a single piece of wood covered by hundreds of layers of lacquer, shows many animals, both mythical and real.

This wooden female figure, made for a malagan ceremony that celebrates the deceased in New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, is playing the katoviso, a type of panpipe. The pandan leaf hat and skirt made of snakes indicate the sculpture celebrates a female ancestor.

****

Related Activities

****

Collaborate with wood

Take a look at George Morrison’s Collage IX at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, or click here to see a picture of it on Mia's website. As a class, make a collage using only wood and glue. Find scraps of wood at home or outside (like sticks and branches). Together, decide where the different pieces look best. Before gluing the pieces onto a plywood board, discuss your decisions. Consider if any revisions would make the work even better.

Wood Search!

At the Minneapolis Institute of Art, hundreds of art objects are made from wood or depict wood (for example, a painting that includes a wooden chair). use the search feature on Mia's website to find art made of wood from different continents, countries, and cultures. Share your favorites with friends and family!

Cut once, measure twice

Click here to watch a You Tube video of Mark Sfirri demonstrating how he makes multi-axis artworks. Then, create your own multi-axis artwork by cutting the tubes from toilet paper and paper towels at diagonals and piecing them together along new axes. If you make enough of them, arrange your multi-axis artworks into interesting combinations. What could you name your creation?

The sound of wood

Borrow wooden musical instruments from a music teacher or bring them from home. If possible, compare the sounds of a wooden instrument to a plastic or metal one (e.g., xylophone to metallophone, wood block to cowbell, wooden drum to bass drum, wooden recorder to plastic recorder). What words could you use to describe the sounds made by wooden instruments? How do these compare with the sounds made by the metal or plastic instruments?

Global wood

Wood is an important renewable resource around the world. Almost every culture has depended on wood for survival, using it for shelter, tools, and fuel. Using a blank world map, locate major forests around the world. Find out the primary type of trees found in each forest (such as pine, oak, cypress, or mahogany) and what is being done—or not done—to preserve this natural resource.

Write about woods

Research poems about wood from a variety of countries and cultures. Then write a poem or haiku about wood, a tree, or a forest. Include words referring to wood, such as grain, whorl, branch, stick, trunk, carve, and cut."